Norhan Allam: “Searching for Zahra was, in essence, a search for historical justice—history cannot be written on anecdotes alone

”Cairo –Maii Abdo:

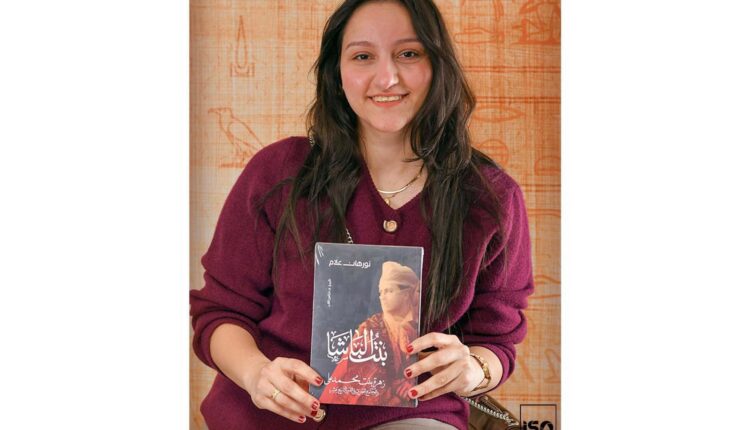

At the headquarters of the Journalists’ Syndicate—where history meets the written word—the conversation with researcher Norhan Allam Salem unfolded like an excavation of a long-silenced memory.

She was not simply recounting the story of a forgotten princess, but addressing a deeper question: how history itself is written, and how dominant narratives often spotlight prominent figures while leaving those in their shadow unseen.A writer and researcher devoted to Egypt’s social history, Norhan represents a generation unwilling to accept inherited narratives without scrutiny.

Although she graduated from the Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, specializing in laboratory sciences, and has worked in the medical field since, her early passion for Arabic language, literature, and poetry continued alongside her scientific career. This dual path later led her to study anthropology, earning a diploma in the humanities. She is currently pursuing her master’s degree, seeking to bridge methodological rigor with critical human insight.Her literary beginnings date back to 2019, when she published her short novel One Minute, Please.

In 2020, she volunteered at a children’s school in Indonesia—an experience she describes as transformative. It inspired her to write a travel narrative submitted to the Ibn Battuta Prize, where it received critical praise, though it has yet to be published. Still, the defining shift in her research journey occurred in Cairo.In November 2020, she joined the “Sirat Cairo” initiative, dedicated to cleaning and preserving archaeological sites. There, her relationship with the city changed profoundly.

Cairo was no longer merely a place of residence; it became a living historical text to be read and interpreted. She recalls this period as a “magical entry point into the world of history,” where her awareness sharpened around the silences embedded within Egypt’s collective memory.The seed of her major research project emerged unexpectedly.

While reading An Artist in Egypt, a work of travel literature, she encountered a brief reference to “Zahra, daughter of Muhammad Ali Pasha,” described as his youngest daughter.

The mention startled her. Despite extensive scholarship on Muhammad Ali as the founder of modern Egypt, his daughters were conspicuously absent from mainstream historical narratives. How could they be missing altogether?When she raised the question during a seminar, specialists dismissed the name “Zahra,” some even doubting the traveler’s credibility.

Rather than discouraging her, this skepticism fueled her determination. Over four years, she examined Arabic and foreign sources, cross-referenced accounts, and pieced together fragmented records. Eventually, she confirmed that “Zahra” was in fact a third name for Princess Khadija Nazli, daughter of Muhammad Ali Pasha.What began as curiosity became a fully realized research endeavor—not only to establish the existence of a historical figure, but to interrogate the reasons behind her erasure.

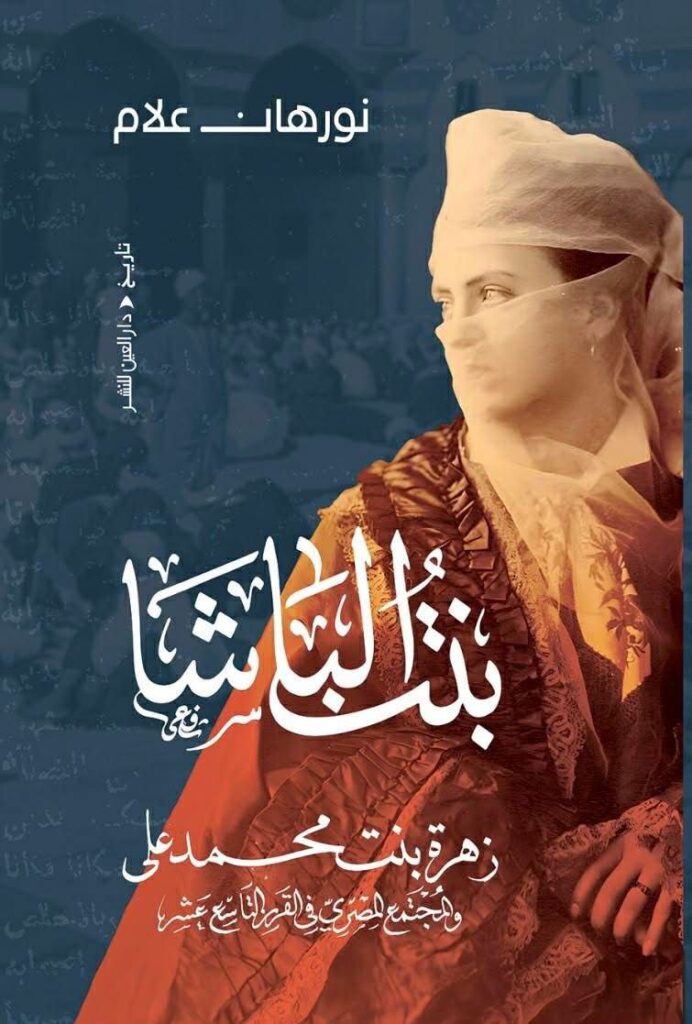

Her book explores the life of Princess Khadija Nazli, also known as Zahra, as a case study in historical marginalization. It investigates why she faded from public memory and reassesses the accusations associated with her, asking whether they arose during her lifetime or were constructed later. The work situates these claims within their political and social contexts, questioning how and why certain narratives endure.

Beyond biography, the book addresses broader historiographical issues, including the scarcity and fragility of Arabic sources from the early nineteenth century and the risks of relying on travel literature as definitive historical evidence. It also examines how political and social shifts contributed to sidelining particular figures—especially women within Muhammad Ali’s household—under an official narrative that glorified the ruler while neglecting his familial sphere.

Norhan pays particular attention to the “harem” as a historically obscured space, inadequately documented and therefore susceptible to reinterpretation through European Orientalist imagination. Such portrayals often dramatized palace women’s lives in ways that aligned with colonial discourse. In this framework, Zahra was not merely forgotten; she became subject to a narrative that reshaped her story according to external stereotypes about the East.

In the book’s opening chapters, Norhan seeks to construct what she calls a “personal history” of the princess—grounded in verifiable evidence rather than oral lore or embellished tales. By assembling scattered references, she attempts to restore coherence and fairness to Zahra’s historical image.For Norhan, recovering forgotten female figures is not an academic indulgence but an epistemological imperative. History, she argues, is not fixed; it is continually open to reinterpretation.

By revisiting established accounts and posing new questions, we expand our understanding of the past and challenge assumptions long taken for granted.She maintains that Princess Khadija Nazli was far more than a silent presence in a palace. Though her influence may not have been overt, she was embedded within the intricate social and political networks of a formative period in Egypt’s modern history.

By the conclusion of the conversation, it was evident that Norhan’s project transcends the rehabilitation of a single historical figure. It is a broader defense of memory’s right to equity. Her work calls for a reexamination of nineteenth-century Egypt through a social and human lens—one that exposes what official histories omitted and questions Orientalist narratives that shaped perceptions of the region.

Her book, The Pasha’s Daughter: Zahra, Daughter of Muhammad Ali and Egyptian Society in the Nineteenth Century, stands as a thoughtful attempt to address a gap in historical consciousness. It seeks to recover a nearly lost female voice and to offer a balanced, critical perspective on the writing of modern Egyptian history.

Norhan speaks not simply as a researcher who completed a manuscript, but as someone who believes that inquiry itself can be a form of resistance. Four years of investigation were not merely about tracing a forgotten name; they were about reaffirming the principle of historical justice.By choosing to explore the margins and illuminate the overlooked, she restores humanity to the center of the historical narrative.

Her work reminds us that history is not a closed chapter, but an ongoing dialogue—reshaped each time we dare to question it. In searching for Zahra, she was ultimately searching for a larger truth: that every era contains voices worthy of remembrance.